And what if you discovered Paris through the eyes and gestures of an Art Nouveau decorative painter?

This is precisely what Artemisia offers through an itinerary that can be done in half a day!

Artemisia is a school based in the 19th district of Paris, which trains its learners in the decorative painting trades through practice.

This guide, part of a European project supported and funded by Erasmus+, will allow you to take a free walk through a few emblematic places, favorites or hidden corners, chosen for their decorative, historical or inspiring potential.

Each step is accessible on foot and illustrated in this leaflet: keep your eyes open, the walk begins here.

Petit Palais

122 Avenue Wiston-Churchill – 75008 Paris

Built to represent the glory of the Fine Arts in France (alongside the Grand Palais, the Pont Alexandre III, and metro line 1) for the 1900 World’s Fair, the Petit Palais is a masterpiece of the architecture of its time. It was designed by Charles Girault, who also directed its construction as well as that of the Grand Palais.

Since 1902, the building has housed the Musée des Beaux-Arts of the City of Paris, which displays, among other things, an impressive collection of 19th-century art.

As a construction, the Petit Palais is part of the Art Nouveau movement, which asserted the unity of art and influenced most fields of creation, from the grandest to the smallest.

A multitude of trades came together to bring this creation to life:

Stonecutters, metal carpenters, carpenters, masons, marble workers, staff makers, stucco workers, mosaicists, art ironworkers, fresco painters, decorative painters, fine artists, gilders, sculptors, stained glass artists, glassmakers – all gathered on this monumental work to innovate and represent Art Nouveau through bold creations, blending Baroque classicism with fantasy and exoticism, reviving a creative universe that was running out of breath.

The Petit Palais is itself a museum of the decorative gesture, but it also houses paintings, furniture, and objects from the final years of the 19th century.

The painter can find sources of inspiration there:

- Painting techniques: this period abounds with Pre-Raphaelite, Symbolist, Impressionist, and Nabi movements

- Purely decorative motifs with acanthus leaves (a heritage from the past), curves, vegetal and animal elements, arabesques, moldings

- Associations of colors with one another

- Wood and wood marquetry

- A sense of asymmetry and pictorial composition

- Style influences

- Forms and compositions of mosaics

- The alliance of several materials

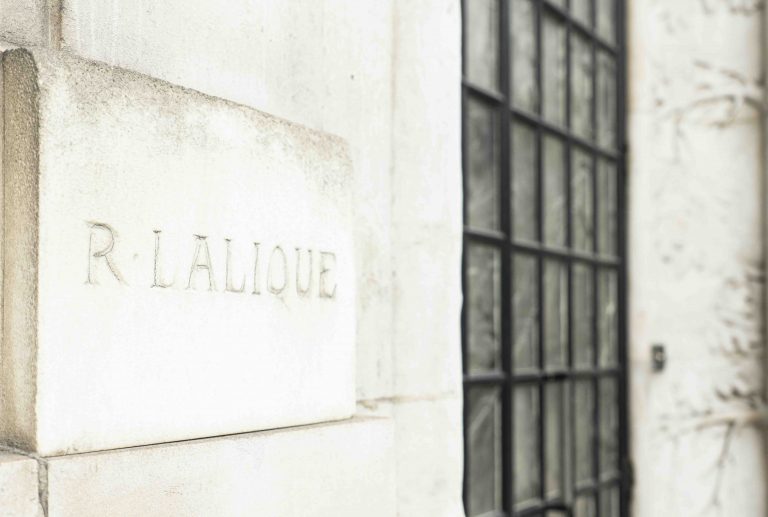

Hôtel Lalique

40 Cours Albert 1er, 75008 Paris

The Hôtel was built by the architect Louis Feine (1868–1949) for René Lalique (1860–1945). Lalique was a renowned glassmaker and jeweler of the time, first noticed by Emile Gallé. He exhibited his works at the 1900 World’s Fair, where he achieved great success among upper-class ladies. Following the Art Nouveau movement, he drew inspiration from nature – flora and fauna – to create his works. His preferred materials were glass, mother-of-pearl, horn, and enamels.

His private mansion was both his residence and his workshop, as well as his exhibition space.

The façade of the Hôtel is inspired by Gothic architecture: it is narrow, tall, pierced with many windows, built entirely of cut stone, and adorned with vertical ornaments on the roof that give the building an even more slender appearance.

However, several decorative elements are of Art Nouveau influence.

This mixture of styles reflects two different eras of the 19th century:

The classical, neo-Gothic influence, and a recognition of the colossal work of the architect Viollet-le-Duc

The Art Nouveau influence, which René Lalique fully embraced through his art, bearing witness to a period that highlighted all the decorative arts

Unlike the architectural asymmetry of Art Nouveau, this building shows rigor and rigidity in its architecture, with each floor respected, numerous identical openings, parallel and tall, giving the façade a very vertical aspect, emphasized by the roof windows themselves framed on each side by stone gables.

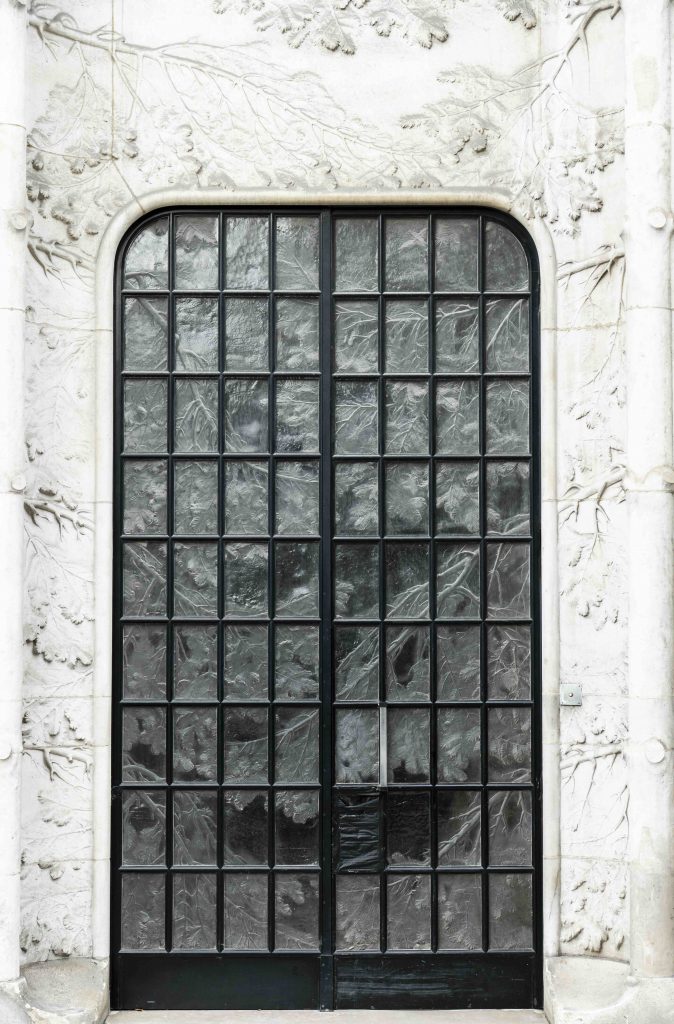

The Art Nouveau influence lies in the ornaments of the railings and the solid stone balustrade: the elements are decorated with intertwined floral motifs, more specifically pine branches with their clusters of needles, in the same way as the entrance door of the building, designed by Lalique himself.

The door is framed on each side by a pine tree (trunks with branches), whose branches extend above the door and up to the first floor.

The innovation of this design is that it does not stop at the glass of the door: Lalique extended the branches onto the glass itself, molded directly into the body of the glass.

Immeuble Lavirotte

29 Avenue Rapp, 75007 Paris

The building is located just steps away from the Eiffel Tower, built for a World’s Fair eleven years earlier, in 1889 (celebrating the centenary of the French Revolution). The building was constructed in the area where the 1900 World’s Fair took place, a highly sought-after location at the time.

Let us recall that the first World’s Fair was held in 1855 in France, followed by others (1867, 1878, 1889), with the last one in 1900, which brought together the achievements of a century of technology and art. Paris, then called the “capital of the arts,” was determined to preserve this title and strongly aspired to become the “capital of the world.” The 1900 World’s Fair covered an area of 200 hectares, stretching from central Paris to the Bois de Vincennes.

This building bears the name of the architect who designed it. It was constructed between 1900 and 1901 and won the prize for the most beautiful façade in Paris in 1901.

Jules Lavirotte (1864–1929) was one of the leading Art Nouveau architects, alongside Hector Guimard.

The commissioner was Alexandre Bigot, a highly renowned and sought-after ceramicist of the time. He was also very open to innovation, new ideas, and imaginative approaches in architecture. His close collaboration with Lavirotte—two artist-craftsmen passionate about this new movement—produced a building that was highly creative, full of imagination, yet still deeply romantic.

Bigot turned this façade into a true open-air catalogue of Art Nouveau ceramics. It served as excellent publicity for his enterprise.

The architecture:

At first glance, the building blends in with the surrounding buildings and rooftops, keeping the same height and following the number of floors of Haussmannian buildings (six floors). In this way, Lavirotte preserved the heritage of the past, also attentive to maintaining an aesthetic unity as Haussmann had intended a few decades earlier. Likewise, he used cut stone from Île-de-France for the ground floor and the first floor, materials typical of Haussmannian buildings.

The second and third floors, as well as the roof, are clad in ceramics. The colors create a gentle blend between stone tones and brick, two materials widely used at the time.

These other floors display an irregular and asymmetrical architecture characteristic of this new movement:

Windows may be rectangular, arched, oval, and of varying widths

A loggia supported by columns

An architectural arch connecting two floors

An asymmetrical and whimsical roof

The fifth floor incorporated into the roof

Unusual dormer windows at roof level

Balustrades in stone, wrought iron, concrete, or ceramic

Balconies of different shapes or depths

Protruding architecture with varying degrees of emphasis

The décor

The façade is covered with ceramic tiles traced with curved patterns (half-circle effects).

Ceramic squares decorate the ceilings of the loggias, each with a flower at its center reminiscent of the classical acanthus flower that adorned ceilings in the temples of Ancient Greece and Rome, though here the interpretation appears more stylized and again plays on curves, so dear to Art Nouveau.

Similarly, the acanthus leaves in ceramic have a freer style, with more pronounced curves.

Every architectural element is adorned with one or several vegetal or animal ornaments.

Certain lines highlight the architecture by emphasizing curves, including wrought iron grilles ending in S-shapes.

Nothing is left aside to showcase the dexterity of the ceramicist; he uses a very free, imaginative, and creative style, sometimes even exuberant. We find there:

Bestiary: imaginary monsters such as dragons, leviathans (doors)

insects

birds (family)

fox

pheasants

cat

lizard (door)

oxenFlora: flower buds

acanthus flowers

acanthus leaves

vegetal forms resembling seaweedFigures: adolescent boy and girl

grotesques

woman’s headCartouches

Columns decorated with motifs of Egyptian inspiration

Castel Béranger

122 Avenue Wiston-Churchill – 75008 Paris

Designed by Hector Guimard (1867–1942)

An Art Nouveau building; the first rental apartment building at a moderate rent. Originally, it was called “Castel Fournier,” after its commissioner.

The neighborhood was very different from today: it contained many small factories and modest warehouses. The local population was mainly made up of artisans, shopkeepers, and workers. The gentrification of this part of Auteuil would only begin about ten years later with the opening of the metro line.

To create it, Guimard drew inspiration from certain architectural and decorative principles of Viollet-le-Duc, from whom he had learned, but he was also influenced by Victor Horta, the Art Nouveau architect and decorator in Belgium.

From the influence of these two architects, he himself gained great renown.

This building made him immediately famous; he received the 1st prize in the façade competition of the City of Paris.

The architecture itself is sober, but the openings and the metal decoration are significant.

The façades of this building are asymmetrical (setbacks and projections), made up of different materials (brick, stone, ceramics, wrought iron, glass), different colors, and different shapes.

The Castel is a hybrid building:

The structure features strong straight lines despite its projections, recesses, and overhangs. Its style carries neo-Gothic influences through its verticality and steeply pitched gabled walls.

At the same time, the building shows great creativity in its ornamentation. There is much of the fantasy typical of Art Nouveau: numerous asymmetrical windows at different heights; curved-line ornaments; grotesques; monsters; real or fantastic animals; arabesques; and reinterpreted acanthus leaves.

The metal ornaments, in antique bronze, seem to emerge from the walls like sudden apparitions, imaginary animals resembling dragons.

The street-facing windows are sometimes rectangular, sometimes ending in arches, with ceramics highlighting the tops of certain windows, framed in metal.

The railings and balustrades in metal are decorated with ornaments that are at times simple, at times sophisticated.

The entrance door, framed by two columns with bases and capitals full of decorative fantasy, is set within a large semicircular arch. The door itself is a play of interwoven curves resembling long plants bent by the wind, supporting a plaque bearing the name of the building.

The entrance appears almost like a grotto, where metal frameworks and ceramics meet side by side.

Hôtel Guimard

122 Avenue Mozart, 75016 Paris

The building is part of the Auteuil neighborhood.

Hector Guimard (1867–1942) married the American painter Adeline Oppenheim, daughter of a wealthy New York banker, in 1909. This private mansion was a gift to his wife.

The building is in the Art Nouveau style, but more classical, more “restrained,” and more bourgeois as well. It belongs to a series of buildings Guimard designed that were comfortable, spacious, and filled with light.

After the 1903 Housing Exhibition, Guimard, who believed he had fully succeeded, showed a certain vanity that was not well received. His activity diminished considerably. It was thanks to his friend, the industrialist Léon Nozal, that he was able to resume his work; however, his style shifted and evolved, becoming less eccentric and more classical.

The Hôtel Guimard was built ten years after the Castel Béranger. It is elegant and discreet in its exterior decoration.

In 1910, Guimard set up his agency on the ground floor, but the couple only moved in two years later because Guimard was making all the furniture. Madame Guimard was able to paint there, as Guimard arranged the third floor as a studio for her.

The exterior architecture: It was built on a small triangular plot of land with a very narrow angle; its shape is therefore unusual, but Guimard managed to make full use of the space.

The façades are in brick, sober, with openings highlighted by another material: stone. These openings come in varied shapes, numerous and of different sizes; they animate the surface of the façade and carry the ornamentation. Elements representing foam are sculpted around or above the windows in stone, executed with great delicacy.

The stone frame of the entrance door depicts garlands of foam on either side of a kind of crest, where the architect’s monogram is carved, thus highlighting his signature.

The wrought iron railings are also highly decorative.

All of the ornamental features are typical of the Art Nouveau movement, with large curved lines around doors and windows (foam, monogram, railings), but also protruding façades and the irregularity of windows according to their function inside the private mansion.

Recent Posts

- International Conference on Tolerance and Social Inclusion Held at Smiltene Technical School

- CCC Project at Smiltene Technical School – Connecting Culture, Craft, and Citizenship

- Latvian Symbol trail “CCC Taka” officially opened in Kalnamuiža

- Culture’s impact on youth – Smiltene technical school students join CCC discussion

- How cultural rights, creative practices and access to cultural life can play a decisive role